It’s 1993. A newspaper headline reads: “Property taken for a fast ride: Ouvah Highfields took millions from developers and went bust inside a year. Chris Blackhurst reports”.

History tends to repeat itself. The flexible workspace industry is no exception.

Let’s stay in 1993 a moment longer.

In one year – 1992 – he (Mr. McCormack) and his main company, Ouvah Highfields, took the commercial property market by storm. He struck deals with some of Britain’s biggest landlords and most prominent tycoons, including Land Securities, Lord Hanson’s Hanson Properties, Sir Allen Sheppard’s Grand Metropolitan, the Duke of Westminster’s Grosvenor Estates, and Cheverell Estates, part of Lord Sterling’s P&O. Mr McCormack’s company took leases on some of Britain’s best commercial properties. These included the old Reader’s Digest headquarters at 7-9 Old Bailey, Swan Court, and 150 The Minories, all in central London, and Salford Quays in Manchester.

In 12 months, Ouvah turned from a small company with a few offices, into Europe’s largest serviced office operator, into a burnt-out shell. Today it is in the hands of the Official Receiver and Mr McCormack has been declared bankrupt.

Sound slightly familiar? Fast-forward to 2010, when WeWork was founded and opened the doors to its first location in SoHo. Fast-forward again to January, 2012; WeWork closes its first angel round with US$6.85 million. Six months later, WeWork raises US$17 million in a Series A funding round. Less than a year later, May 2013, the company raises US$40 million in a Series B funding round. February 2014, another US$150 million comes pouring in from a Series C funding round. Just 10 months later, the company raises a whopping US$355 million in a Series D–the deal valued the company at US$5 billion.

From then on, WeWork was on a roll, raising large amounts of money, attracting some of the world’s biggest investors, and continuously increasing the company’s valuation.

Today, the coworking company has a US$20 billion valuation, something unheard of both in the serviced workspace industry and the real-estate industry. In less than 5 years WeWork became the largest coworking brand and the most-valued company in the industry, ever.

WeWork’s valuation has long been a topic of debate. The same can be said for its financial model. For a few years now, industry experts have expressed their doubts and concerns regarding WeWork, in particular worrying that the coworking giant was creating a bubble that would be hard, if not impossible, to sustain.

It’s a modern version of Ouvah. And the stakes are higher.

“Ouvah took an office building from the landlord at an agreed rent. It would then break up the building into smaller units and re-let them, usually to small businesses,” The Independent reported back in 1993.

“WeWork takes on long-term leases for raw office space and builds out the interior with flexible workspaces and modern design that it then subleases for terms as short as a month,” The Wall Street Journal wrote a few days ago (link has paywall).

“In return for taking the building off its hands, the landlord normally granted Ouvah a six-month rental holiday. Sometimes, the landlord would also make a payment to cover the fitting out of the building,” The Independent article continues.

“I don’t take three months rent free, I take more like 12,” said Adam Neumann, WeWork CEO, about his negotiations with landlords during an interview with The Telegraph.

“At first, the scheme appeared to work well,” The Independent article continues. “The hard sell meant that, even in the depths of recession, Ouvah found tenants. But they were often paying rents far below the going rate.(…)the low rents were explained away on the basis that they would increase and eventually match the going rate. Unfortunately, that did not happen.”

In June, 2016, leaked documents of WeWork showed that the company was not performing nearly as well as it had originally projected. “Their internal financial review for the month of April showed that they slashed their 2016 profit forecast by 78%, their revenue estimate by 14%, and reported a 63% surge in negative cash flow,” Allwork.Space wrote in an article at the time.

Just as it was with Ouvah, revenue projections were not met and the company was not able to sustain its growth without incurring significant losses.

Just recently, “Mr. Minson, the finance chief, said WeWork doesn’t expect profitability this year. In 2014 it had projected it would have income of $500 million by now. Mr. Minson said WeWork could be profitable tomorrow if it weren’t investing so much in growth,” The Wall Street Journal reported.

Keep in mind the amount of funds WeWork has raised from investors and the fact that they are still not paying any rent on some of their locations — this last part also allows them to offer prices that no other competitor can match, which means WeWork has been dumping.

The WSJ article also reported that “vacancy rates have risen recently, and the company is increasing incentives to draw tenants.”

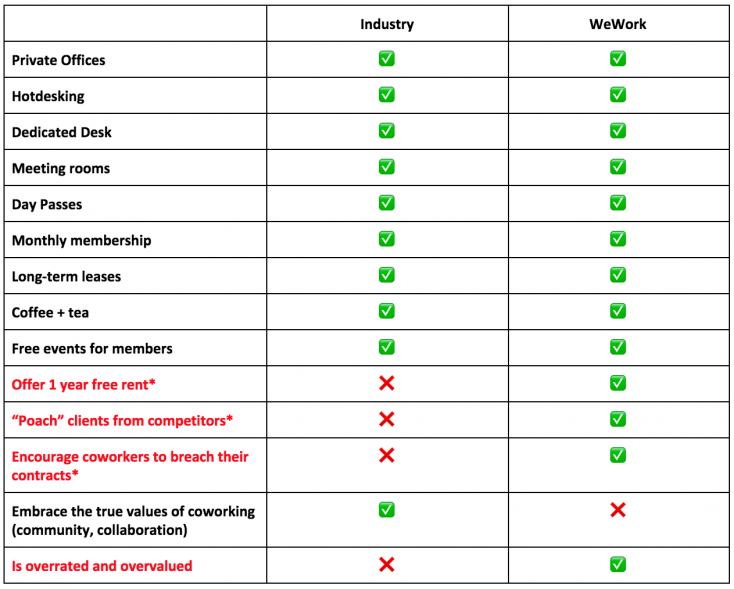

Increasing incentives is a nice way of putting it. WeWork has been using questionable tactics for poaching clients, and it’s also been cannibalizing the industry. You can read more about that here:

- Is WeWork Cannibalizing The Industry With The Classic Bait-And-Switch Tactic?

- Desperate Times Call For Desperate Measures: How Low Will WeWork Go?

- WeWork Poaching Episode 3: The One Where They Go After A Coworking Space Owner

Ouvah went bust once landlords realized the serviced office company was not going to be able to pay rent after the ‘free-rent’ period expired.

“Just before Ouvah went into receivership, Mr McCormack sold it to Colin Youell, a London property financier, for an undisclosed sum,” reads The Independent article.

“Mr. Neumann has told friends and associates he has sold more than $100 million of WeWork’s shares,” The WSJ reported.

Taking into consideration WeWork’s Finance Chief’s recent statements about not making a profit, seeing WeWork’s desperate attempts at attracting new clients to fill up its spaces, and Neumann’s claimed sale of shares, the question is: Is WeWork headed in the same direction as Ouvah? Is WeWork’s bubble finally bursting, and if it is, what does it mean for the industry at large?

And Just For Fun: How The Coworking Industry Operates vs. WeWork

*Evidence (video, images, email) of these claims can be found on the following link.