- The pandemic brought less pollution and CO² emissions, and more animals came out in cities and towns around the world to reclaim what is left of their habitat.

- Long before Covid-19, our destructive behavior of abusing the earth for consumer purposes had been exponentially growing. This is also known as the Plastic Age.

- Royce Epstein shares how a material evolution is necessary for the design industry to heal our relationship with nature and create design solutions for the future.

This article was originally published on Work Design Magazine.

With a new decade upon us a year ago, we had a lot of hope for 2020. This was going to be the start of a new era where material evolution and climate change would be addressed widely in industries from construction, manufacturing, energy, farming, etc. In our own design industry, there have been urgent calls to decarbonize, since decarbonized buildings contribute almost half of the carbon dioxide emissions in the United States alone.

The AIA issued the 2030 Commitment to transform how architecture can become carbon neutral. Large design firms like Gensler have also made similar commitments. And then came the pandemic.

While the whole world went sideways, we started to see nature repair itself. We saw less pollution and CO² emissions, and we saw more animals come out in cities and towns around the world to reclaim what is left of their habitat.

But the pandemic had major setbacks for sustainability as well: disposable PPE, more single use plastics, and disruption to recycling and take-back programs.

Long before COVID-19, our destructive behavior of abusing the earth for consumer purposes had been exponentially growing. This is also known as the Plastic Age, where the infiltration of everlasting plastic is in our oceans, our landfills, our food, and water supplies, and in all living species. This is but one environmental crisis, and much of this has happened since the industrial revolution but more crucially since the advent of plastics in the mid-century.

Plastic was once seen as a hopeful and futuristic material, where we could make things that are durable, lightweight, and long-lasting. And yet today, plastic has become a divisive material, so often seen as cheap, disposable, and polluting with toxic raw materials. The longevity of the material is exactly its most challenging problem – scientists believe it takes about 1,000 years for plastic to degrade in landfill.

This is where the material evolution comes in, as we seek progress with the exploration of new materials for a new decarbonized age within the Anthropocene. This is the current era we live in, where there is evidence of mankind’s damage to the planet. This is seen as a marker for environmental change, where plastics are cohabitating with natural phenomena in a new form of pollution.

We can move to a new consumption model where materiality is an important change agent for good. Designers are seeking new materials, new processes for making, and participating themselves in a democratic way. We don’t have to rely on change to come, we can create it ourselves as activism. We are seeing this happen in the field of materials as a call to action through restorative design, so that we may heal the relationship with nature and create design solutions for the future.

So how do we move forward? Let’s identify what must be done:

- First and foremost, we must realize and act on the idea that we all are making things that impact generations to come, unless we embrace design and materials intentionally designed for the short term (such as those that biodegrade).

- When we create new materials from waste or from newer healthier ingredients, we are creating a new value on the objects made from these components. These need to be the new design currency. Circularity is critical, where the end of life of one material becomes the source material for another. This is how nature works, and as humans we should be thinking in this biophilic way.

- Materials need to be dematerialized. Their carbon footprint needs to be reduced or eliminated through the raw materials used, the manufacturing process, and the transportation and distribution of the final products, as well as what happens at the end of life of that product/material. This is known as embodied carbon and moving forward, we need to be reducing this as much as possible.

- Materials need to be rethought, remade, and remanufactured with new ideas and processes to address over-consumption and the burden of stuff. Using waste and upcycled materials is important as an interim step, but the major goal is to eliminate materials that do not biodegrade as they become the fossils of the future (plastic, we are looking at you).

- Materials need to be healthy and have transparency on how they are made. We need to shift to low or no-impact materials that have no chemicals of concern for damage to humans or natural habitats.

How can the material evolution redesign the Plastic Age? For a new generation of emerging designers, sustainability is becoming an ingrained part of their education and practice. One new practice of design is “Bio-Based”, where designers are looking for natural alternatives to synthetic, oil-based materials that do not biodegrade, hence the great challenge of plastic.

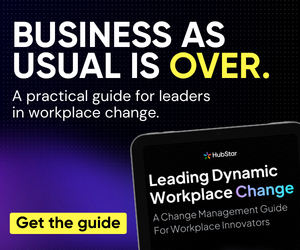

Biological fabrication (or bio fabrication and bio-facturing) can replace manufacturing of synthetic materials. The global bioplastics industry is optimistic and growing, with both manufacturers and consumers demanding plastic-free goods in all sectors such as cosmetics, food packaging, clothing, household goods, interior and construction materials, and beyond.

We have entered a new era of design called “Disruptive Materiality”, where designers are cross pollinating with biosciences to reinvent materials as we currently know them. This also gives new life for farmers, who can collaborate with scientists and designers to harvest these raw materials.

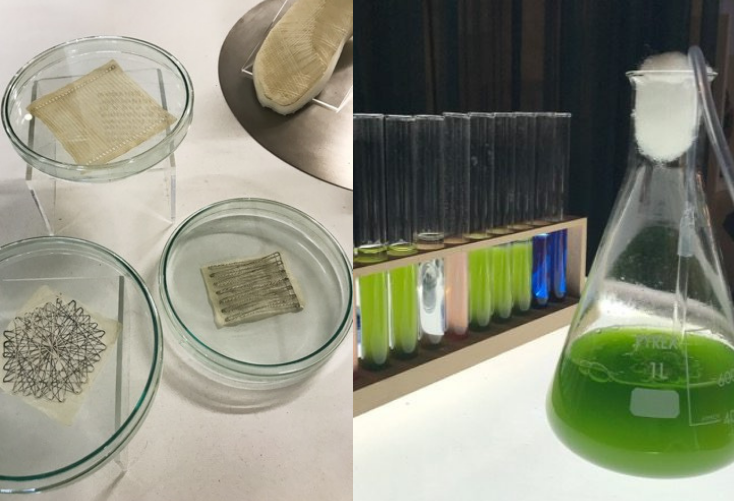

Natural resources such as algae, kelp, crustaceans, sugar cane, potato and corn starch, mycelium (mushroom), and microbes are all used to make bioplastics. Some, like algae, grow in abundance due to global warming. Other living organisms, like bacteria and fungi, can be grown into the shape of lighting, furniture, sneakers, or created as biopolymers, which can be woven into textiles. And some are waste materials from the agriculture and seafood industries. These materials are biodegradable and often compostable. They are not designed to last for hundreds of years; they are designed for normal consumer use and then they return to nature at end of consumer use.

With the advent of bioplastics, we can start moving towards a post-plastic world. According to research at WGSN, the global bioplastics industry is forecast to reach a market value of over 35 billion dollars by 2022. This suggests growing economic interest in bioplastics, and also confirms the desire by consumers for these new materials.

But we are not there yet.

Today there are over five trillion pieces of plastic floating in the ocean, and manufacturers are still making stuff from virgin plastic. The goal here is to learn from and harness the intelligence of nature to create new materials that are regenerative rather than destructive. This is a model all about future possibilities, and more and more designers and businesses are working towards this goal that can be restorative rather than about short-term use and disposal.

While we are still facing uncertainty and global turmoil, one thing is clear: we can never abandon hope when there is much work to be done. Both the planet and humanity must sustain for there to be a future.

We are fortunate to have incredible advances in technology during this time of great change, and yet we also fall short of sustaining a healthy planet and population. We have all collectively damaged the planet, and now as designers, makers, and manufacturers, we have a responsibility to incorporate best practices for making products and built spaces that are healthy for occupants and the environment alike. What will you do?

Further reading:

- Recipes for Material Activism by Dr. Miriam Ribul – open source on Issuu.com

- Radical Matter: Rethinking Materials for a Sustainable Future by Kate Franklin, Caroline Till

- Why Materials Matter by Seetal Solanki

- Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival by Paola Antonelli, Ala Tannir

- The Secrets of Bioplastics by Clara Davis – available on Issuu.com

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky – The Office Whisperer

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky – The Office Whisperer Nirit Cohen – WorkFutures

Nirit Cohen – WorkFutures Angela Howard – Culture Expert

Angela Howard – Culture Expert Drew Jones – Design & Innovation

Drew Jones – Design & Innovation Jonathan Price – CRE & Flex Expert

Jonathan Price – CRE & Flex Expert