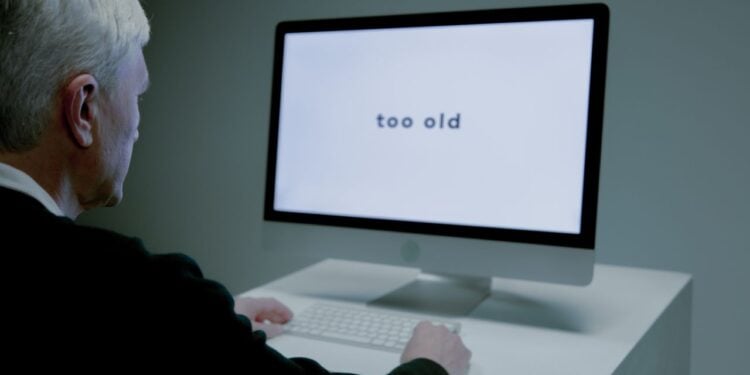

- Before the pandemic, an AARP survey showed 61% of people ages 40 to 65 had either seen or experienced ageism in the workplace. In May of 2021 that number jumped to 78%.

- In a Q&A with Allwork.Space, Patti Temple Rocks, author of I’m STILL Not Done: It’s Time to Talk About Ageism in the Workplace, shared how organizations who engage in ageism are putting themselves at risk and missing out on valuable contributions from an experienced talent pool.

- She says that all companies need to create and enforce hiring and employment policies to reduce ageism.

Ageism in the workplace can go either way, and it’s no joke.

Age discrimination occurs when a manager or boss treats an applicant or employee less favorably due to their age, which applies to younger people with less experience as well as older people who are close to retirement age.

More than 80% of hiring managers say that they are concerned about taking on employees 60+, or younger than 25.

Before the pandemic, an AARP survey showed 61% of people ages 40 to 65 had either seen or experienced ageism in the workplace. In May of 2021 that number jumped to 78% — the highest number AARP has ever recorded since they began tracking in 2003.

In a Q&A with Allwork.Space, Patti Temple Rocks, author of I’m STILL Not Done: It’s Time to Talk About Ageism in the Workplace, shared how organizations who engage in ageism are putting themselves at risk and missing out on valuable contributions from an experienced talent pool.

Allwork.Space: What are the hidden costs of turnover that companies are risking by excluding workers over 50?

Patti Temple Rocks: There are many costs of turnover, but only some of them can be measured with a dollar sign. But let’s start with those. The average cost of a discrimination claim is $125,000 if the employee and company choose to settle. If there is no settlement, the median cost of litigation is roughly $200,000 and 25% result in judgments that exceed $500,000. These figures don’t include defense costs, which are typically significant because the average duration of age discrimination matters is 275 days. Those are the average cases. Age discrimination can, however, in some circumstances, be much costlier — in the multi-millions.

But here are those hidden costs you ask about:

In addition to the actual costs of litigation, you also must consider the not-insignificant soft costs of age discrimination. These are often hidden and include workplace distractions and loss of productivity for your HR and legal teams, as well as your executives, who must take time out of their days to deal with these allegations.

Even if an employee doesn’t file a claim but is merely alleging age discrimination, HR and legal will likely investigate the allegation as a best practice. This means your HR and legal teams’ valuable time will be spent interviewing people and reviewing relevant emails rather than on something that would probably be more positive and beneficial for your organization.

But here, in my opinion, is the most damaging hidden cost of all: even if a claim is not made public, it’s usually no secret to the rest of the organization. It can therefore also significantly impact employee morale. When an employee feels another employee might not have been treated fairly and with respect, it can’t help but impact how they feel about the organization — and not in a good way.

Allwork.Space: What steps can leaders take to create an anti-ageism organization?

Patti Temple Rocks: In my book I write about 10 steps an organization can take to create positive change regarding ageism, because I believe strongly that this is a “fixable” problem. I will share three of those steps that I believe are essential and will create meaningful change – and quickly.

First, look inward. There are many good leaders who simply haven’t been paying attention and don’t realize that the unconscious bias in their organization is leading to ageist behavior. There are quantitative things you can do — like conduct an employee census to determine if the ages of your employees mirror the ages of the population at large.

Do an audit of your external positioning. Does your website show only young people? On the softer, qualitative front, the best thing a leader can do is talk to older workers and ask them about their experiences working for the company. It’s easy to think it isn’t happening here, but chances are, it is. Once leaders are enlightened (and yes, I am an avowed glass-half-full thinker) they can begin to eradicate ageism in their organization.

Second, make eradicating ageism a priority — and do so visibly. Your senior leadership team and human resources team both need to make the ageism discussion a priority. If HR isn’t paying attention, they should be, but chances are that they aren’t.

According to Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM), less than one-third of HR departments have analyzed the impact of older workers leaving over the next three to five years, and only 17% have looked at that over a six- to ten-year horizon.

All companies need to create and enforce hiring and employment policies to reduce ageism. They should ensure that ALL employees — including older ones — have opportunities for training and development. All information should be defined, visible to employees, and clearly stated in the employee handbook and code of conduct.

Third, have the conversation. It’s that simple: have the conversation. The difficult conversation about a planned end to a career almost never happens, but it’s time that it starts happening.

It is very difficult, if not risky, for an employee to initiate a conversation about a desire to retire in the next say, one to three years. They understandably fear that their employee may (unfairly) question their commitment to their job or the company. They worry that their company may have no strategy or practice for any sort of planned retirement — because most don’t. So consciously or not, we often think “I’m just going to shut my mouth and keep my head down for as long as I can” — which is, at best, very stressful!

And on the other side of the conversation, many supervisors don’t initiate it because they are afraid they might say the wrong thing, or they feel awkward about it and worry that what they say might lead to litigation — or something else unpleasant. While it’s an excuse, it’s understandable.

But the result leads to a lose/lose situation. The conversation simply doesn’t happen and too often decisions about the end of an employee’s career are made based on stereotypes and false assumptions.

Make the commitment to have the conversation about what’s next with all your employees over 50. The best advice I ever received about that came from a trusted colleague from human resources who says to have it with EVERY employee. Consistently asking every employee once a year, “How do you want to learn, grow and develop in the next 12 months?” If you have that conversation, introducing the retirement conversation will be much easier.

Allwork.Space: What are some strategies for dealing with an employer who is trying to force a premature retirement?

Patti Temple Rocks: With my rose-colored glasses firmly in place, I believe it is at least worth asking the question of “why?” Is the company in financial trouble? Does my supervisor think I want to retire? Has there been a change in direction or strategy that might be driving this? Of course, none of this is an acceptable excuse for forcing anyone out of the organization, but it always helps to understand what is really going on, and perhaps you can negotiate a win-win.

Maybe you are ready to trade in some salary for greater flexibility in hours or location. Maybe the manager is incorrectly assuming that a new direction for the company doesn’t match your strengths or interests and you can show him/her how wrong they are.

But…with my glass now half empty, my advice is all about protecting yourself and to acknowledge your company might be ageist in attitude and behavior and discriminating against you in ways that are legally protected.

At this point you need to document everything that you are seeing and feeling. Take great notes and indicate dates and times of all conversations. You should also formalize your concern with a written complaint to HR. Although you need to be careful about revealing too much, it is always a good practice to talk with colleagues about what they are seeing and observing.

Rarely is ageism a one-off; it is usually a pattern of behavior that points to an ageist organization. There may indeed come a point where it is time to get professional advice from an employment attorney you trust.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky – The Office Whisperer

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky – The Office Whisperer Nirit Cohen – WorkFutures

Nirit Cohen – WorkFutures Angela Howard – Culture Expert

Angela Howard – Culture Expert Drew Jones – Design & Innovation

Drew Jones – Design & Innovation Jonathan Price – CRE & Flex Expert

Jonathan Price – CRE & Flex Expert