- Designers are using AI to reveal what the future of the built environment could look like.

- The living building — a structure that symbioses with nature — will play an important role.

- Ancient materials and methods are the key when it comes to making living buildings a reality.

Although the concept might seem new, biophilia — the human race’s innate desire to connect with the natural world — has been inspiring the design of manufactured environments for thousands of years.

Biophilic design encapsulates much more than potted plants and living walls: it is realized through the use of natural light, texture, smell and sounds from nature.

You could argue that for a building to be wholly biophilic in design, it must symbiose with the environment in which it exists. Waste does not exist in nature; everything is cyclical, unlike the linear models of production that underpin capitalist society.

Construction today typically follows this linear trajectory: materials are extracted, transported, produced, transported again, and used to build and fit out. Then, when elements of the building are no longer required, they are sent to landfill.

Of course, there have always been exceptions.

And with the environment straining under the impacts of human-induced climate change, developers, architects, designers and operators are increasingly adopting new (and old) construction practices that are symbiotic and sustainable.

Visualizing living buildings

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being used to demonstrate what a world populated with living buildings could look like.

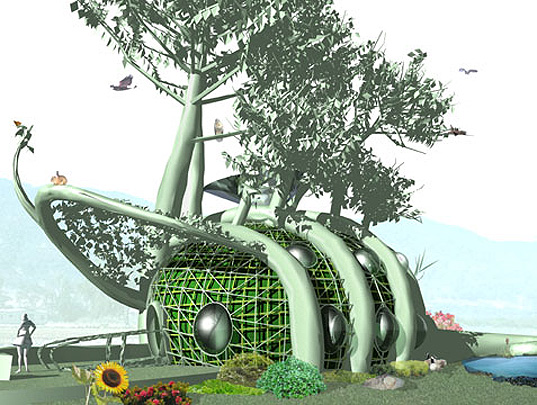

In a project titled Symbiotic Architecture, designer Manas Bhatia uses the AI tool Midjourney to create visuals for what living buildings might look like in the context of the real world.

The text-based prompts Bhatia used to create the images in Midjourney are inspired by both nature and architecture, and include “giant,” “hollowed,” “tree,” “stairs,” “facade,” and “plants.”

View this post on Instagram

At MIT in 2005, architects Mitchell Joachim, Javier Arbona and Lara Greden developed a hypothetical ecological home named Fab Tree Hab. The idea was to think outside of existing construction conventions to imagine a space that could form part of nature’s ecosystem.

Using the past as a source of inspiration

The Fab Tree Hab team utilized contemporary technology and drew on old methods.

They proposed that the structure of the living building be formed by enabling native trees to grow over a CNC (computer designed) plywood scaffold.

This support mechanism could be removed after the branches of the tree had been weaved together using the ancient technique of pleaching, which dates as far back as Roman times.

Architect Yasmeen Lari also draws on Roman methods in their work.

In 2005 an earthquake in Kashmir—one of the most destructive in modern times—killed over 80,000 people and rendered 3.5 million without a home. In response, Lari created a blueprint for a locally sourced and biodegradable shelter built using a local mud construction method.

Lari has trained thousands of people in how to set up the shelters, through the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan and YouTube tutorials.

As well as mud, the shelters use lime — a material used by the Romans to make concrete.

Lime is formed by heating limestone, a process that releases carbon and leaves calcium oxide. When combined with water, the lime reabsorbs the carbon from the atmosphere.

Sustainable construction materials

Every day, researchers are working out ways to make buildings more symbiotic. In recent years, for example, they have been exploring mycelium as a material for construction.

Mycelium is the root network of fungus. It can grow quickly and easily on coffee grounds and other matter. It is already being used to make packaging and clothes, as well as furniture, insulation and bricks for use in the construction industry.

Mycelium is low-cost, low-density and has a low carbon footprint. It can also biodegrade and provides quality thermal and acoustic insulation.

Hempcrete is another example of a biocomposite that can be used in place of concrete and “traditional” forms of insulation. Certified commercial farmers can grow industrial hemp, and it is created by mixing the hemp with lime and water.

Hemp plants are adept at absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and like mycelium, the production and application of hempcrete is low-carbon. Hempcrete walls are better at insulating than other insulation options, so occupiers can reduce their energy consumption.

Then there is ferrock, which combines waste steel dust with silica.

When exposed to carbon dioxide, ferrock hardens and traps carbon dioxide. It is stronger than concrete and can be used for underwater construction projects.

Unfortunately, ferrock is not yet suitable for large-scale projects; because it relies on the availability of recycled materials, there is limited availability.

The offices of the near-future are symbiotic

The offices we work in must become more environmentally aligned. Buildings that are passive, linear or not making attempts to adapt are already falling out of favor.

The desire for architecture to do better is widespread: 83% of employees want to see a more environmentally friendly office, according to Essity’s research.

If a company’s product is net zero, but it rents or leases a carbon intensive building, it cannot call itself net zero. Net zero means zero carbon emissions across the supply chain, so the onus is also on workspace providers to make their buildings more sustainable.

There are a range of living/green building certifications to take advantage of today.

Getting accredited can help an organization to identify what it needs to do to become more environmentally aligned. It also encourages accountability, as good certifications require frequent auditing (for example, every three years) to ensure continuity.