- What caused the millennial wealth gap?

- How are millennials responding?

- What does this mean for the economy at large?

Ah, millennials. The public seems obsessed with this demographic born between circa 1981 and 1996 with many stereotypes surrounding this generation.

Some say they’re snowflakes.

Others say they’re entitled.

(Few mention that millennial income levels are woefully poor compared to previous generations.)

And millennials aren’t alone in the generational mud-slinging match. Research from the Harvard Business Review suggests that “workplaces are brimming with age-related stereotypes and meta-stereotypes, and that these beliefs are not always accurate or aligned.” Additionally, “Older and younger workers believe others view them more negatively than they actually do.”

Whether aimed at the old or the young, such ageist labels are inaccurate at best.

Research reveals that millennials are better educated than prior generations.

In fact, a greater proportion of millennials and Gen X (the 1965 to 1980 birth bracket) are also in the workforce, compared to any previous generation.

But education and employment does not equal economic control (or success) for today’s millennials.

In 2016, older millennials were 40% poorer than previous generations were at the same stage of life.

Overall, the average millennial is $36,000 in debt and one-in-five will never pay off their debts.

Yet, millennials are considerably less attracted to seeking credit than preceding generations. Instead, they’re a generation that’s notoriously wary of financial institutions.

However, money is often needed to fund a higher education, especially in the United States. . The Federal Reserve notes that student loan balances have reached their highest levels in history.

Millennials also have considerably less control of the economy, compared to previous generations.

Research reveals that despite making up the largest portion of the US workforce, millennials controlled just 4.6% of the country’s wealth in the first half of 2020.

But boomers (those born between 1946-1964 ) control more than half of the country’s wealth. Gen X holds just over a quarter.

The silent generation (born in 1945 and before) holds around 17%.

Of course, it’s not unusual for older generations to hold the bulk of the wealth. They have, after all, had more time to establish their careers and save some money.

But here’s the problem.

In 1989, when the boomers were roughly the same age as today’s millennials, they controlled more than 20% of the nation’s wealth.

That’s more than four times as much as what millennials own today.

This isn’t just a one-off finding.

Report after report cites that the millennial generation is (to quote one piece in The Washington Post) “the unluckiest generation in U.S. history”.

There are many reasons for this situation.

For starters, the economy is an ever-changing system. Historically, some generations (arguably) have had better opportunities than others thanks to conditions that were outside of their control.

Yes, boomers and Gen Z. I hear you.

You worked hard too. Every generation has. And every generation has its own unique set of challenges. That includes you. And millennials.

“If you look back 20, 40 or 60 years, the same pattern of differences shows up again and again,” says David Costanza, who co-authored an influential study on generational differences in 2015. “The youngest generation is always the least dedicated, the least satisfied and the most mobile. Twenty years ago, that was Generation X. Forty years ago, it was the boomers. Now it’s the millennials.”

We could argue the work ethic of each generation until the cows come home. (Or should that be until the avocado gets smashed on the toast?)

But there’s one thing that no one can deny.

A vast wealth gap now exists between millennials and baby boomers – with some arguing that it’s too late to close the divide.

“Millennials are running out of time to build wealth,” warns this Bloomberg report. “Fewer millennials own homes than their parents did at their age. They have more debt – especially student debt. They simply aren’t as wealthy.”

But the times, they are a-changin’.

Other sources claim millennials are catching up with other generations in terms of their financial clout.

Are ‘the snowflakes’ about to kick up a storm?

If so, how exactly?

Let’s find out.

What caused the millennial wealth gap?

The average millennial income currently stands at $47,000 per annum.

The typical millennial household only has around $28,000 in net worth (according to 2016 figures) – putting them 40% behind what previous generations had in wealth at the same age (in inflation-adjusted terms).

But there are many factors that come into play when you start to dig into millennial income levels.

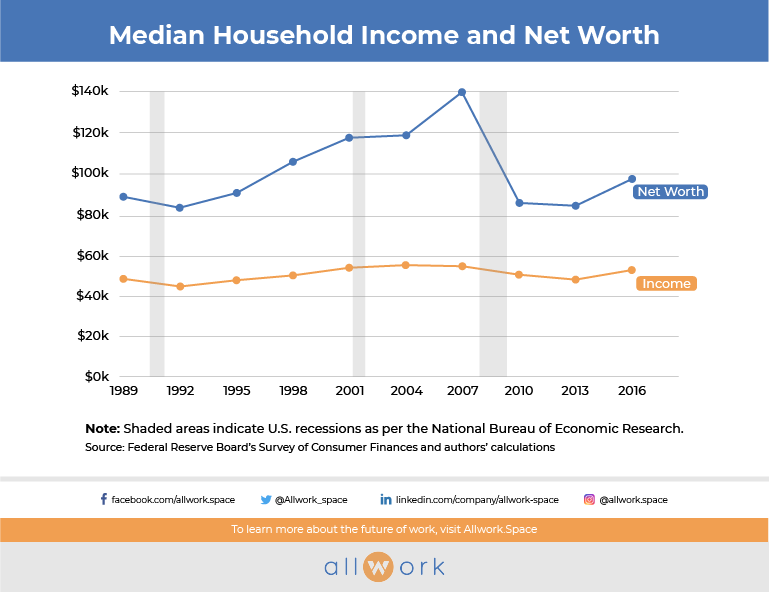

Let’s start with the Great Recession. This had a major impact on the millennial income vs baby boomer’s wealth gap.

In the last 30 years, the U.S. economy has been hit by three recessions. But the Great Recession between 2007 and 2009 hit especially hard.

Compared to the dot-com bubble burst in 2001 and the savings and loan crisis from 1990 to 1991, the net worth of the average American household fell much more steeply during the Great Recession.

In other words, families suffered deep and widespread losses – with young families the worst hit, according to research from New America.

The report states:

“Recovery between 2010 and 2016 is evident for most birth decades. Income recovered by an average of 15 percentage points while wealth recovered by 7 percentage points on average. However, gains were not shared equally. Older cohorts, measured by the typical family, fared better on both income and wealth recoveries.”

Why?

Well, when the Great Recession came, many millennials were just coming of age and entering the world of work. As such, the sweeping economic downturn hit millennials harder than their parents, as they had fewer savings and assets on which to rely.

More than 50% of millennials have less than $5,000 in savings.

In short, millennials lost their economic footing.

Low-interest rates exacerbated the issue, increasing asset values – including stocks, bonds and housing.

Baby boomers were able to capitalize on this, purchasing those types of assets thanks to the savings they had already squirreled away.

Of course, that’s a move any financially savvy individual would make. But many millennials were not yet at an age where purchasing those types of assets was common – or even possible.

This had a cumulative effect.

As more assets were bought up by older generations, millennials were left struggling to afford the same purchases. Prices went up. Millennial income levels could not match these increases.

House prices also increased due to urbanization. This further increased the wealth gap.

Millennials were unable to afford houses at the age their parents were. Because of this, they were forced to rent longer, depleting their savings without providing equity. Alternatively, a growing number of millennials chose to live at home with their parents.

“It’s not just homes. Millennials have been reluctant to buy items such as cars, music and luxury goods. Instead, they’re turning to a new set of services that provide access to products without the burdens of ownership, giving rise to what’s being called a ‘sharing economy’,” according to Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research.

That’s not all.

Baby boomers have also enjoyed a period of influence over the last couple of decades.

Because they have different views on economics, they vote in ways that often result in increased hardship for millennials, who don’t face the same economic conditions their parents did.

“What boomers want, boomers get,” writes Helen Lewis in The Atlantic. “Older voters warp their countries’ policies because of their political power.”

“The trouble was the sheer number of boomers. As a big generation, the boomers had achieved political and cultural dominance. They were no more self-interested than any other group, but they warped government priorities. And that was unfair to everyone else.”

But we’re now at a tipping point.

As many millennials turn 40, they’re starting to infiltrate the positions of power. And there are now more millennials than ever.

In the US, there are now 92 million millennials and 77 million baby boomers.

Millennials are also predicted to be the wealthiest generation in history by some sources.

The kids are growing up fast – but they’re still not OK.

And they’re starting to push back – in new and innovative ways.

How are millennials responding?

Millennials are responding in many ways to address the wealth gap, delaying many of the traditional milestones that previous generations chose.

Let’s start by looking at the housing market.

The peak home-buying years are between 25- and 45-years-old, the current age bracket of most millennials.

But many millennials are reluctant to enter the housing market, with the majority of 18- to 35-year-olds living with their parents in order to save money.

The recent pandemic exacerbated issues. Some 9% of young adults said they relocated due to COVID-19, with 10% having somebody move into their house.

Why?

Well, homes now cost millennials 14 times more than the boomer generation.

By avoiding (or reducing) rent, millennials can now save up for a house deposit, despite having comparably lower wages than their parents had at the same age.

Right?

Not necessarily.

“Millennials are getting screwed again by their second housing crisis in 12 years,” according to one report in Business Insider.

“Now that they have economically recovered and are looking to buy a home for the first time, we’re faced with this housing shortage,” Daryl Fairweather, the chief economist at real estate brokerage Redfin, told Insider. “They’re already boxed out of the housing market.”

Oh dear.

It looks like the millennial income bracket can’t stretch far enough for this generation to become homeowners.

And this millennial income percentile calculator shows how income rates change with age. Here, you can also see how millennial income by state differs too.

Across the board, things look bleak for millennial income levels.

It’s not just interest in housing that’s plummeting for millennials – so are marriage rates.

Millennials are getting married far later.

In the 1970s, the median marriage age was 23. In the 2010s, it was 30.

They’re also waiting longer to have children. Nearly 13% of women were having children by the age of 25 in the 1970s. In the 2010s, it’s less than 8%.

At the age of 35, that figure shifts to 3.6% of women in the 1970s and 6% in the 2010s.

In doing so, millennials avoid having to pay for weddings, children and their associated costs.

This also ties into the reluctance to buy houses and get married – the financial instability many millennials face is leading them down different paths.

Millennials also purchase less.

They are less likely to buy home items such as a new TV just because new models appear on the market. They buy less clothes than their older Gen X peers.

But there is one area where they splash the cash – millennials reportedly value experiences over possessions and spend more on travel than any other age group.

Wellness is also important to millennials. They’re exercising more. They’re eating better — and smoking and drinking less, compared to previous generations.

Millennials are also exploring multiple ways to earn some extra money. Many are leveraging technology and other avenues to access side hustles. They start companies, sign up for freelance gigs, and create online content to supplement their incomes.

Research reveals that 64% of millennials have a side hustle. That’s compared to 44% of boomers and 58% of Gen X.

When asked “why side hustle?” each demographic gave a very telling response.

The majority of Gen X and boomers wanted to make additional money to spend on leisure activities, like sporting events or vacations.

Millennials?

The vast majority wanted to generate additional income to add to savings.

All this hard work is starting to pay off.

In the last three years, older millennials are hitting 40 and have made significant gains in their wealth and are now only 11% below expectations.

Further research into millennial income statistics reveals that UK millennials increased their collective earnings to a record £254 billion last year, as boomer incomes fell.

The tide is starting to turn.

And it’s starting to turn because millennials are taking a new approach to many traditional ways of living and working.

They’re entrepreneurs. They’re gig economists.

They’re disrupting traditional markets and ways of life.

And they’re starting to impact the economy.

What does this mean for the economy?

Just as millennials are finding new methods (and shunning old traditions) to save money – the economy is being impacted in several ways by this generation.

First, we have the sharing economy.

With so many being unable to outright purchase previously essential goods, the economy has moved towards a more flexible model. A sharing one.

Let’s explain what we mean here. The sharing economy is simply built around sharing resources. Instead of buying a car, you rent one. But it’s a two-way street. When your car isn’t being used, you can rent it out to someone too.

And get paid.

Same goes for your house. Or your bike.

It’s the foundation on which Airbnb and its counterparts are built on.

These rent-based services are heavily utilized by millennials. Rather than buy things like cars or houses, millennials now turn to sharing apps that allow access to these goods when needed, without the expense of ownership.

Research reveals that a growing percentage of older millennials are choosing to rent, not buy. While 52% rented in 2005, this figure increased to 60% by 2013.

For some, this sharing model will end up with the world living in some rent-based dystopia.

“The year is 2070. Nobody owns a home anymore; the concept of individuals possessing property has gone the way of the floppy disk,” writes Arwa Mahdawi for The Guardian. “Instead, a few large corporations control all the world’s real estate and people ‘subscribe’ to holistic housing solutions on their iPhone 78X in the same way they currently subscribe to Netflix.”

However, the sharing economy has the flexibility today’s millennials need, helping them save for the future and monetize their existing assets.

We’re also seeing the maturing sharing economy start to nibble away at the B2B market.

“The B2B sharing economy offers compelling economic, social, and ecological benefits. By wisely sharing their tangible resources and intangible assets with each other, purpose-driven businesses can make immense gains in efficiency and agility and positively contribute to communities and the planet,” writes Navi Radjou in Fast Company.

Gig work is also skyrocketing – where workers get paid for individual short-term chunks of work or “gigs” they do.

The gig economy is an umbrella term. You can be a freelancer, part-time worker or contractor, for example. But it basically means a temporary job with short-term arrangements between an individual and organization. Uber is a classic example here.

On the surface, it’s a good deal for employers and workers. Employers get a wider talent pool. There aren’t any recruitment or employment costs. Workers can choose projects that interest them, as and when they want to.

The term “be your own boss” has just got a millennial upgrade.

And with fewer millennials able to secure traditional careers, there has been a boom in such work.

Two-thirds of full-time employees intend to leave jobs for a gig.

The gig economy is predicted to grow three times faster than the traditional workforce.

As millennials continue down this path, it is likely they will vote to reform laws around benefits and create an environment that is more supportive of gig workers.

We’ve already seen Uber drivers in the UK are now entitled to workers’ rights.

But gigs are not always the best option.

Around 85% of gig workers reportedly earn less than $500 per month.

That’s not all.

“From the outside, freelancing seems like a dream: You work when you want to work; you’re ostensibly in control of your own destiny. But if you’re a freelancer, you’re familiar with the dark side of these ‘benefits.’ The ‘freedom to set your own hours’ also means the ‘freedom to pay for your own healthcare’,” writes Anne Helen Petersen for BuzzFeed.

We’ve also seen an increase in reskilling and upskilling as people try out new gigs (and careers).

That’s because learning and development are important to millennials.

Research reveals that reskilling/upskilling opportunities are the most important benefit to 42% of millennials, when deciding on their next career move.

“Contrary to popular opinion, most millennials surveyed do not want to constantly change jobs but feel frustrated by the lack of opportunities to develop their skills and meet their career aspirations,” according to one report.

Here, technology has opened the door to boundless gigging opportunities for many millennials. Anyone can start an online shop, blog or business with a few keyboard taps, for example.

In the UK, millennials are also the country’s most prevalent entrepreneurs, setting up 50% of new businesses since July 2020. The stats are the same in the US – half of all new businesses were set up by the millennial generation.

As millennials easily adapted to remote work, the pandemic has accelerated this trend.

When it comes to house prices, many are predicting a crash as millennials cannot afford to buy up the housing stock as older generations move on. But the predicted crash isn’t expected any time soon.

“Without the market having much time to catch its breath, the 7% to 8% increases of the past year will only moderate as the mania for property as an investment marches onwards,” writes Phillip Inman in The Guardian.

But maybe these material assets don’t mean much to millennials anyway.

Research from Deloitte reveals that millennials have a strong social conscience:

More than half donate to charities

44% made choices over the type of work they were prepared to do or organization they’d work for based on their personal ethics

35% volunteer or are a member of a community organization, charity or non-profit

25% took part in a public demonstration/protest/march

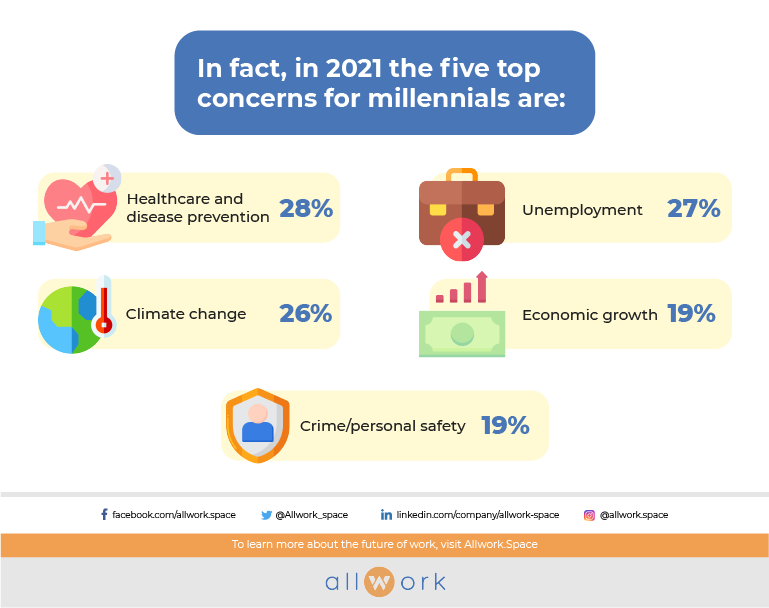

In fact, in 2021 the five top concerns for millennials are:

- Healthcare and disease prevention (28%)

- Unemployment (27%)

- Climate change (26%)

- Economic growth (19%)

- Crime/personal safety (19%)

It’s clear to see how recent events have shaped the millennial generation. They’ve grown up in one of the most financially uncertain periods in recent history.

They’ve had to adapt to new technologies faster than you can say “let’s Zoom”.

They’re lived through three global recessions.

They’ve faced a pandemic.

And now, they’re expected to pick up the pieces with less money than any generation before them.

Conclusion

The economy is always changing.

At the moment, it’s in the middle of a handover between the boomer and millennial generations.

And neither party seems that happy about it.

Maybe, that’s because the global economy isn’t in the best shape now.

But it’ll be the millennial generation that’ll need to make sure the economy is in a fit state for its Gen Z predecessors.

From advancing digitization to the Great Recession and the recent pandemic, just as millennials have not been shaped by a single event, they’re not changing the economy using a single strategy.

They’re gigging. They’re disrupting. They’re starting new businesses and investing in their own health and wellbeing – as well as that of the planet.

According to the Pew Research Center, this is because millennials have minimal confidence in many of the key institutions that make up today’s society. This includes the government, big businesses and law enforcement.

It’s not all gloom and doom for this ‘lost generation.’

Many millennials are thriving and doing quite well financially. According to a recent post in Business Insider, ‘geriatric’ millennials “have the most power in the workforce right now.”

So, yes, the economy is changing thanks to millennials – but so is the wider world.

But the millennials aren’t going to enjoy their moment in the sun for long.

It’s predicted that Gen Z will beat millennials in 10 years’ time and be “the most disruptive generation ever”.

Don’t say we didn’t warn you.

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky – The Office Whisperer

Dr. Gleb Tsipursky – The Office Whisperer Nirit Cohen – WorkFutures

Nirit Cohen – WorkFutures Angela Howard – Culture Expert

Angela Howard – Culture Expert Drew Jones – Design & Innovation

Drew Jones – Design & Innovation Jonathan Price – CRE & Flex Expert

Jonathan Price – CRE & Flex Expert